1 • The “question of questions”

- If God is good, why is there evil?

- If God exists, why are there earthquakes, tsunamis and babies with down syndrome born?

- Why does God allow innocent pain?

Raise your hand if you have never asked yourself one of these questions…

The question about the problem of evil is not “a” question: it is the ultimate monster of questions.

2 • The problem of evil

After an extensive search through the Pthumerian labyrinths (i.e. on Google), I discovered that the issue is so significant that it deserves its own branch of theology (and its own page on Wikipedia), called “theodicy”.

For those who have never pondered the question of God and evil, let me summarize it very briefly:

- that there is evil in the world doesn’t need to be proven (it’s enough to observe it);

- regarding God, there are two options: either He exists or He doesn’t;

- If He exists, it seems that in relation to human He doesn’t intervene. From here, therefore, two options arise:

- Either He is not omnipotent: He would like to intervene, but He cannot;

- Or He is omnipotent: He could intervene, but He chooses not to.

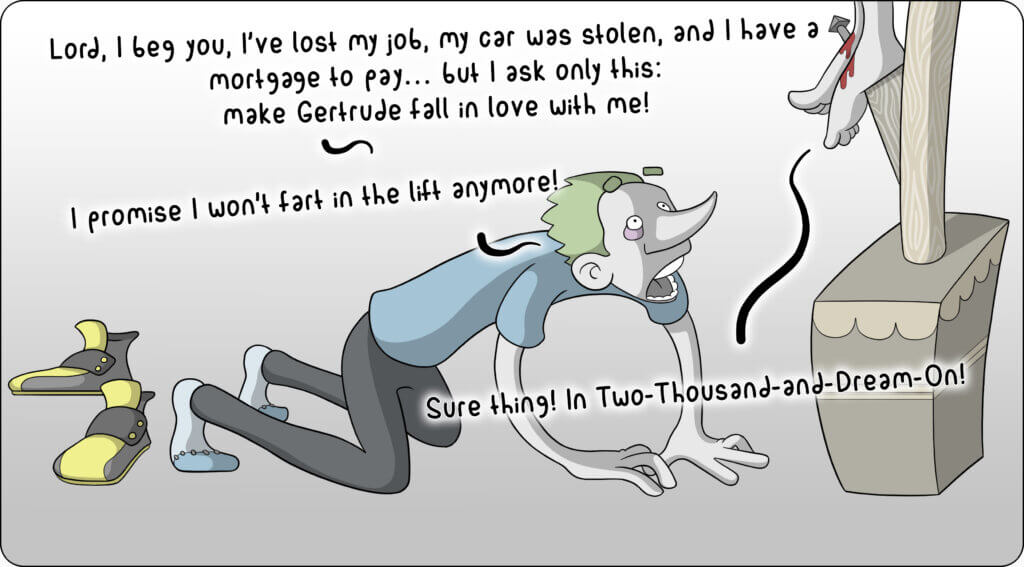

The problem of God and evil has raised many perplexities in the faith journey of many individuals…

…so much so that many, after receiving the “sacrament of Farewell” (a.k.a. Confirmation), not finding an answer to this question, have ended up imagining God as a kind of unjust employer:

3 • The right answer is the… the…

In short, we come to the answer…

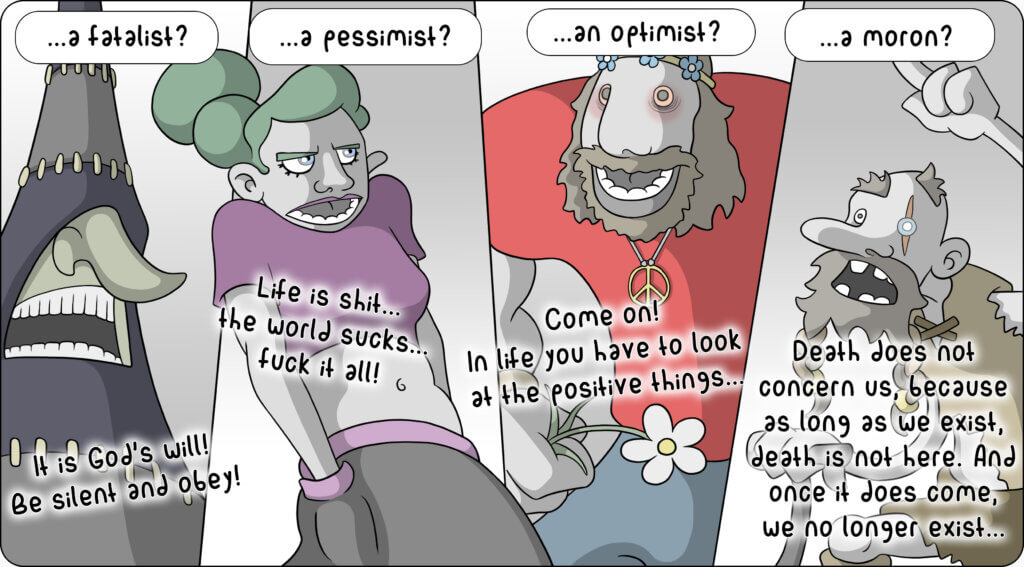

How can one answer, without looking like…

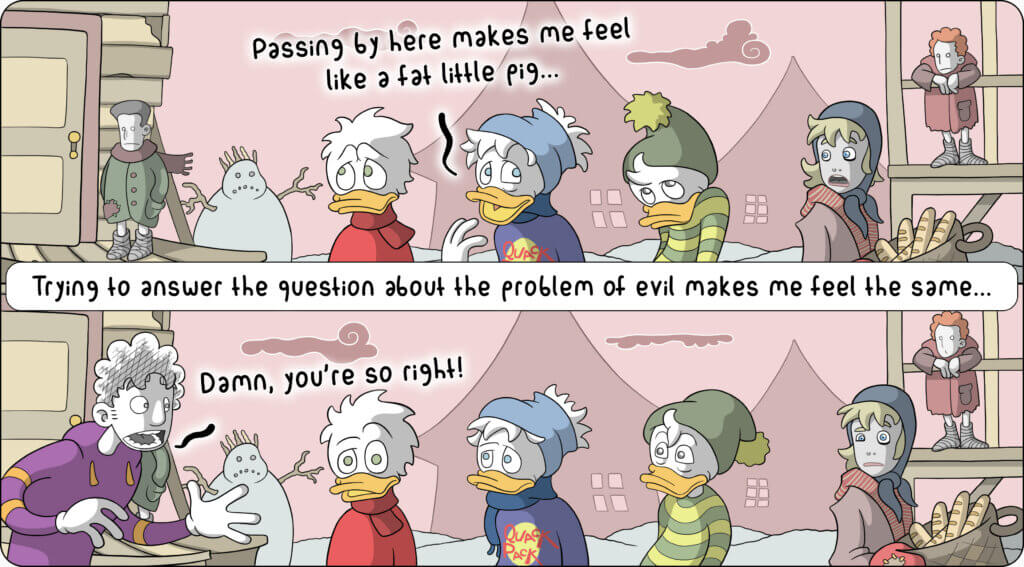

The cartoonist Carl Barks, in 1952, begins the narration of the story “A Christmas For Shacktown” by drawing Huey, Dewey, and Louie strolling through Shacktown, the poor neighborhood of Duckburg.

Walking through those streets and observing all the impoverished families, Huey exclaims:

Paraphrasing what the wise nephew of Donald Duck said, it’s challenging to answer these kinds of questions if you haven’t gotten your hands dirty with suffering.

I mean, you can try.

But then most likely, you’ll receive one of these answers:

- “If you had truly suffered, you wouldn’t say these things…”

- “You’re talking, and at most, you’ve had an ingrown toenail?”

- “What do you know about my sufferings?”

- “With your explanation of why there is evil in the world, I could wash my armpits with it…”

…responses that, for the record, I find righteous and legitimate…

Attempting to explain evil always seems a bit arrogant, forced.

Blasphemous.

In short (just to be clear): I also feel a bit like a chubby pig compared to many sufferings I’ve seen around me but have never personally experienced.

4 • Evil Narrated by the Sufferers

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur said:

Evil cannot be explained; it can only be narrated.

In recent years, in the quest for an answer to the question of the problem of evil, I have come across the stories of some people who have suffered greatly and have decided to put their experience of pain into words.

I discovered the incredible story of Salvatore Crisafulli (see bibliography at the bottom).

That of Adriano Stagnaro (again, in the bibliography), Wanda Półtawska (also in the bibliography).

That of Zack Collie (look for his channel on YouTube).

In this paragraph, however, I want to focus only on a small part of the life of Clive Staples Lewis.

Perhaps you know that Lewis was a rationalistic agnostic who later converted to Christianity around the age of thirty.

To be fair, some of this credit could be attributed to Tolkien (a devout Catholic), who was one of his dear friends…

…by the way, Lewis also participated in the literary discussion circle of the Inklings…

In 1950, Lewis met Joy Davidman. In 1952, the two got married.

However, a few years into their marriage, Joy developed bone cancer and died shortly thereafter.

In the following months, Lewis recorded in a diary all the reflections and moods he experienced day by day: the visceral pain, the labor of mourning, the longing for his wife, the search for a Hope that seemed to dim.

The following year, he decided to publish those pages under the pseudonym N. W. Clerk (in the book “A Grief Observed”).

Here are some phrases from this diary that I’d like to share:

I have always been able to pray for the other dead, and I still do, with some confidence. But when I try to pray for H., I halt. Bewilderment and amazement come over me. I have a ghastly sense of unreality, of speaking into a vacuum about a nonentity.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.22)

…and a little later:

It is easy to say you believe a rope to be strong and sound as long as you are merely using it to cord a box. But suppose you had to hang by that rope over a precipice. Wouldn’t you then first discover how much you really trusted it?

[…]

Only a real risk tests the reality of a belief.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.22)

…and:

For in the only life we know He hurts us beyond our worst fears and beyond all we can imagine.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.22)

Are these sentences a bit too harsh?

Maybe… or maybe not at all… I don’t know…

In any case, Lewis is not afraid to lay bare, before God, his entire being, his fragility, his doubts.

Any form of “bourgeois religiosity” (if there ever was one) has fallen away…

But let’s continue with a few more passages:

No, my real fear is not of materialism. If it were true, we – or what we mistake for ‘we’ – could get out, get from under the harrow. An overdose of sleeping pills would do it.

I am more afraid that we are really rats in a trap. Or, worse still, rats in a laboratory.

[…]

Sooner or later I must face the question in plain language. What reason have we, except our own desperate wishes, to believe that God is, by any standard we can conceive, ‘good’? Doesn’t all the prima facie evidence suggest exactly the opposite? What have we to set against it?

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.24-25)

Throughout the first part of the diary-book, Lewis continues to present these pressing questions (to himself and to God).

Despite the tone and the harshness of the questions, it seems evident to me that Lewis’s is a vibrant faith. A faith in which he certainly suffers, struggles, and is troubled, but always with the intent to seek the truth.

What he is going through is a genuine spiritual struggle.

This tension, this yearning, this uneasiness that he lays bare before God — sometimes posing uncomfortable questions (similar to Job in the Bible) — I believe are very healthy.

Profoundly Christian.

In the face of a certain way of thinking, from bored individuals with a bit too much in their bellies, who think they’ve already figured out everything about religion…

For Lewis, the relationship with God is not an oasis to escape from the problems of the world.

Quite the opposite.

5 • The Calm After the Cry

Let’s read further in the diary:

I wrote that last night. It was a yell rather than a thought. Let me try it over again. Is it rational to believe in a bad God? Anyway, in a God so bad as all that? The Cosmic Sadist, the spiteful imbecile?

I think it is, if nothing else, too anthropomorphic.

When you come to think of it, it is far more anthropomorphic than picturing Him as a grave old king with a long beard. […] Though it is (formally) the picture of a man, it suggests something more than humanity. At the very least it gets in the idea of something older than yourself, something that knows more, something you can’t fathom. It preserves mystery. Therefore room for hope. Therefore room for a dread or awe that needn’t be mere fear of mischief from a spiteful potentate.

But the picture I was building up last night is simply the picture of a man like S.C. — who used to sit next to me at dinner and tell me what he’d been doing to the cats that afternoon. Now a being like S.C., however magnified, couldn’t invent or create or govern anything.

He would set traps and try to bait them. But he’d never have thought of baits like love, or laughter, or daffodils, or a frosty sunset. He make a universe? He couldn’t make a joke, or a bow, or an apology, or a friend.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.25)

And shortly after:

Bridge-players tell me that there must be some money on the game ‘or else people won’t take it seriously.’ Apparently it’s like that.

Your bid—for God or no God, for a good God or the Cosmic Sadist, for eternal life or nonentity—will not be serious if nothing much is staked on it.

And you will never discover how serious it was until the stakes are raised horribly high, until you find that you are playing not for counters or for sixpences but for every penny you have in the world.

Nothing less will shake a man—or at any rate a man like me—out of his merely verbal thinking and his merely notional beliefs. He has to be knocked silly before he comes to his senses. Only torture will bring out the truth. Only under torture does he discover it himself.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.28)

And to conclude:

(one week later)

I am surely, in general, a saner man than I was then. Why should the desperate imaginings of a man dazed—I said it was like being concussed—be especially reliable? […]

All that stuff about the Cosmic Sadist was not so much the expression of thought as of hatred.

I was getting from it the only pleasure a man in anguish can get; the pleasure of hitting back. It was really just Billingsgate—mere abuse; ‘telling God what I thought of Him.’

And of course, as in all abusive language, ‘what I thought’ didn’t mean what I thought true. Only what I thought would offend Him (and His worshippers) most. […] Gets it ‘off your chest.’ You feel better for a moment.

But the mood is no evidence.

Of course the cat will growl and spit at the operator and bite him if she can. But the real question is whether he is a vet or a vivisector. Her bad language throws no light on it one way or the other.

(CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS, A Grief Observed, Harper Collins, London 2015, p.28-29)

6 • … and what does the Bible say?

Some might find Lewis’s statements a bit strong.

They might think these are the thoughts of a Christian who went too far, of a black sheep who doesn’t mince words when expressing his thoughts to God.

(I hope no believer has been somehow disturbed or stiffened by these passages)

In reality, I found them very much in resonance with many passages from the Bible…

Oh, of course, I’m not an exegete!

Nor have I read the Bible in its entirety.

But I’ve had the fortune to dwell on some really beautiful books of the Old Testament…

For the most intrepid, I would suggest reading the Book of Job and Ecclesiastes.

Little by little, though, without overdoing it… just in case…

Here are a few passages:

If I sin, what do I do to you,

you watcher of humanity?

Why have you made me your target?

Why have I become a burden to you?

(Job 7:20)

In my vain life I have seen everything;

there are righteous people who perish in their righteousness,

and there are wicked people who prolong their life in their evildoing.

(Ecclesiastes 7:15)

Why is my pain continuous,

my wound incurable, refusing to be healed?

You have indeed become for me a treacherous brook,

whose waters do not abide!

(Jeremiah 15:18)

Well, what can I say?

They don’t seem very different – both in terms of content and tone – from Lewis’s discourse.

Well, these phrases are found in passages at the end of which Christians – at Mass – say “the word of God”.

Doubt, struggle, resentment towards God are not something “wrong”, “foreign to faith”, that “doesn’t fit well” in a spiritual journey.

Getting angry with God is not in contrast to the Christian revelation (not necessarily, at least).

In short, borrowing a thought from Franco Nembrini:

There are blasphemies that are prayers and prayers that are blasphemies.

(FRANCO NEMBRINI, from his commentary on Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, Canto XIV, Mondadori, 2018, p. 322)

7 • What does Christian Revelation say about evil?

You know that aphorism that occasionally some Christians might say: “everything happens for a reason”?

Well… it’s false!

Or at least, it’s not written anywhere in the Bible, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, or the documents of the Church’s Magisterium…

Then again, I still need to finish reading the Necronomicon…

According to Christian Revelation, God did not create evil.

Evil, from a certain point of view, doesn’t make sense.

That’s precisely why the problem of evil is truly a drama, just as the problem of human freedom is (although it might not seem so, these two issues are actually connected).

Now, the concept of freedom is quite a mess.

Especially in our era, where many of us are (more or less) convinced that “deep down, everything is already predetermined: starting from DNA, through the education we receive, the context we live in, the culture, nationality, etc.”.

(Despite this last notion being a very trendy dogma, in my opinion, I don’t believe in it).

A Pope in the “dark” Middle Ages once said:

We believe that the devil became evil not by predisposition, but by free choice.

(INNOCENT III, 1160-1216)

The same applies to man; indeed, in the so called deposit of the Christian faith, it is contained in this fact: that God created man free.

In the gift of freedom – I believe – there is all the greatness, paradox, and mystery of God’s love.

The “catch” is this: God desires that man loves freely. And to do this, He can only leave him free.

Free to say yes to Him.

Or to refuse.

To choose the good set before him (with all that entails).

Or to reject the good (with all that entails).

In any case…

No, I didn’t say that.

Sooner or later, on the blog, we’ll talk about Hell (whether it exists or not), the Devil (whether it’s a reality or superstition), whether there is a Judgment at the end of life, and other things related to the “Hereafter”…

…but for now, we’re talking about evil “down here” on Earth!

And on this point, Jesus seems quite clear to me:

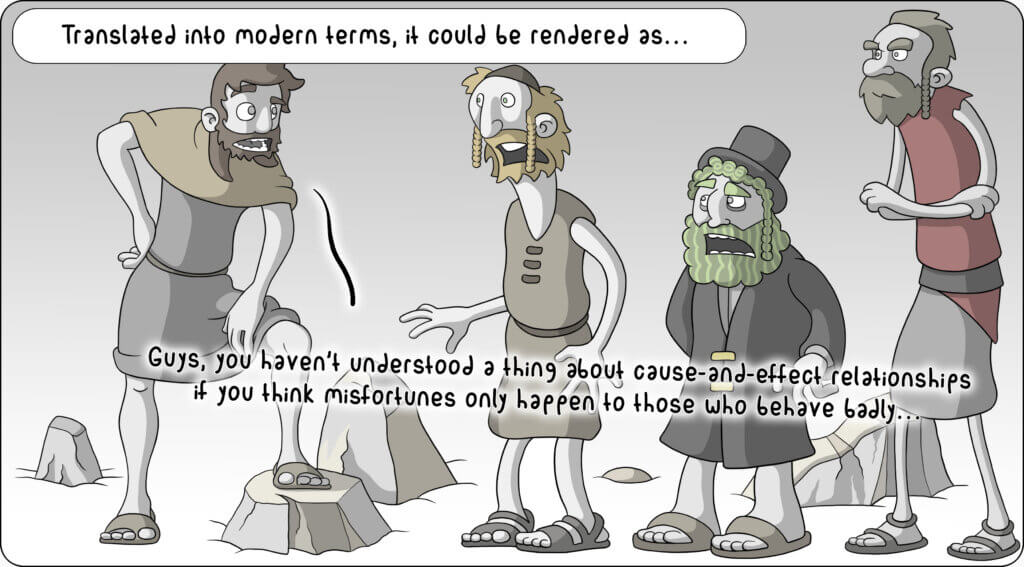

At that time some people who were present there told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with the blood of their sacrifices.

He said to them in reply, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were greater sinners than all other Galileans? By no means! But I tell you, if you do not repent, you will all perish as they did! Or those eighteen people who were killed when the tower at Siloam fell on them 3 – do you think they were more guilty than everyone else who lived in Jerusalem? By no means! But I tell you, if you do not repent, you will all perish as they did!”.

(Luke 13:1-5)

Exactly, Jesus explains – in contrast to a typical way of thinking in his time – that good and evil are not necessarily direct and immediate consequences of our actions.

8 • Jesus and pain

Paul Claudel, the French poet and playwright, wrote:

Jesus did not come to suppress suffering, nor to explain it, but to inhabit it with his presence.

In the previous paragraph, I mentioned that it is not true that “everything happens for a reason”.

However, it is true (IF Christianity is true) that God can bring good out of every situation, no matter how compromised or desperate it may be.

sale

(Spring 2019)