In the following paragraphs, I bring to light other interesting aspects I discovered as I researched the Inquisition courts… particularly how the trials were conducted.

I have divided the information into five paragraphs. If you don’t feel like reading everything, you can click directly on the links below to jump to the paragraph that interests you:

- Typical Behavior of the Courts

- Anonymous Accusations

- Severity of Penalties

- Defendant’s Defense During the Trial

- Use of Torture

For those interested in the number of deaths caused by the Inquisition, I have dedicated another page of the blog to the issue.

1 • Prudence of the Inquisition Courts

Many people believe that in inquisitorial trials the judge had the power to condemn the accused capriciously, depending on their mood that morning…

The jurists of the time unanimously asserted that given the seriousness of the crime of heresy, the guilt of the accused had to be certain. Some did not hesitate to claim that it was better to leave a guilty person unpunished than to condemn an innocent one:

Sanctius enim est facinus impunitum relinquere, quam innocentem condemnare.

(From the 14th-century manual De Officio Inquisitionis, p. 319)

There is ample evidence that the Roman Congregation supervised the implementation of such precautions by the tribunals.

In a series of letters to the nuncio, the archbishop, and the inquisitor of Florence sent in March 1626, the Holy Office tried to curb a witchcraft hysteria epidemic that had led secular authorities to act hastily, seriously compromising the quality of the administration of justice:

…and as daily experience shows, fears in men are far greater than the reality of events, for they are too quick to reduce any illness, whose cause is not immediately known or whose remedy is not readily found, to some form of witchcraft. […] The rumor that in Florence and its countryside there are many witches has no real foundation.

(Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Manoscritto Barb. lat. 6334, f.67v)

The Holy Office then recommended to the nuncio to inform the magistrates that the rumors about the presence of a large number of witches in the countryside were unfounded.

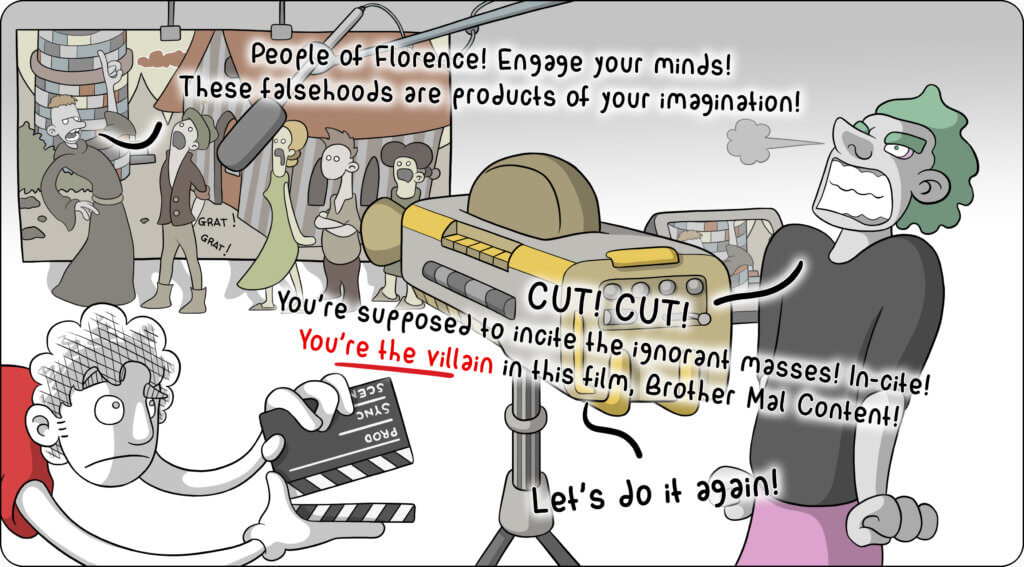

…you see…

…can you imagine the scene in a Hollywood movie?

2 • Anonymous Accusations and Testimonies

Anonymous denunciations and testimonies given without an oath were not considered in the proceedings of the Inquisition trials.

…warning that our precepts will not be satisfied, nor should they be understood as being fulfilled by those who, with bulletins or letters lacking the name and surname of their authors, or in any other uncertain manner (of which no account is taken by the Holy Office), might claim to reveal the offenders.

(“Instructio seu Praxis Inquisitorum”, Francisco Peña, 1605)

Furthermore, at the beginning of the defensive phase of the trial, the accused was asked to name anyone who, in their opinion, might wish them harm. If some of the names belonged to prosecution witnesses, the inquisitor was obliged to further investigate their motivations and credibility, as well as the nature and severity of the hostility between them and the accused (See the Directorium Inquisitorum by Nicolas Eymeric, annotated and expanded edition by Francisco Peña, p. 607).

The numerous convictions for false testimony demonstrate that the verification of the validity of accusations was taken seriously. One can refer to the sentence issued on June 6, 1566, against eight Neapolitans who had unjustly accused Dr. Marco di Rosa of Acerno of heresy. All perjurers were sentenced to the galleys. In the case of Hettore Bussone, who had incited the others, the sentence read: “[…] we condemn you to be publicly whipped in Rome in the usual places […] and then to be sent to the galleys for ten years to serve as a rower”. Additionally, all the calumniators were obligated to pay the expenses and compensate for the damages suffered by their victim (see documents of the Trinity College, ms.1224, f.74).

3 • Severity of Penalties

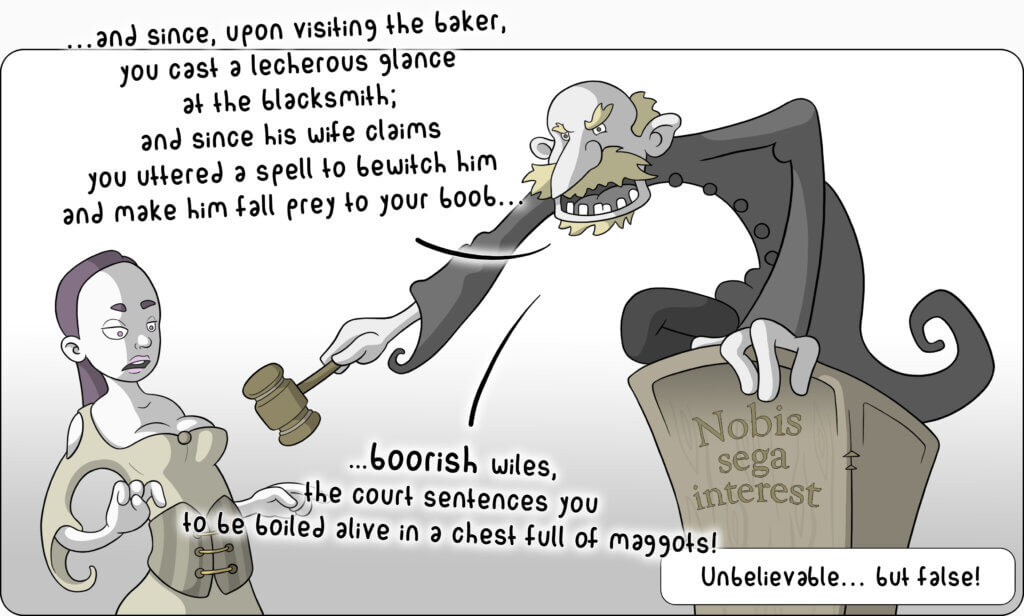

The stake, life imprisonment, and forced labor on the galleys are the horrifying sanctions associated — in people’s imagination — with Inquisition trials.

Unfortunately, here too, reality blends with fantasy:

The examination of hundreds of sentences preserved at Trinity College suggests that, typically, the penalties were much milder. Quite often, forms of public humiliation are encountered, ranging from abjurations read on the steps of the churches on Sundays or other holidays, in front of people going to Mass, to penances in the form of cycles of prayers and devotions, etc…

4 • Defendant’s Defense During the Trial

Numerous historically unreliable blockbusters (off the top of my head, I think of “Season of the Witch” with Nicholas Cage, but there are really plenty) have passed down to us a distorted portrayal of “ecclesiastical jurisdiction”: injustices, carelessness, summary judgments,…

John Tedeschi (in his “The prosecution of Heresy: Collected Studies on the Inquisition in Early Modern Italy”) writes that in secular courts, evidence and indications against the accused were read aloud, and the accused had to construct their defense on the spot.

In the Inquisition courts, however, if after the presentation of evidence and testimonies, and the conclusion of the accused’s interrogation, the accused neither defended themselves nor declared guilt, they were allowed to develop their defense. For this purpose, they received, at their own expense (but free for the indigent), an authentic copy of the transcript of all proceedings up to that point, with the charges (“articuli”) in the vernacular to facilitate understanding (cf. letter from the Commissioner of the Roman Holy Office, Antonio Balduzzi, to the Inquisitor of Bologna, dated September 20, 1572; and also the printed edict, “Ordini da osservarsi da gl’inquisitori, per decreto della Sacra Congregatione del Sant’Officio di Roma” of 1611).

They were then given time to study the evidence against them and prepare questions aimed at refuting the prosecution witnesses. They were allowed to request the testimony of all individuals — excluding close relatives — who, in their opinion, could demonstrate their innocence (cf. “La fase difensiva del processo inquisitoriale del Cardinal Morone; documenti e problemi” by Massimo Firpo, 1986). In cases of the accused’s indigence, the inquisitor was obligated to cover the travel expenses of defense witnesses to the court or the nearest Inquisition official to their residences.

5 • Use of Torture during the Trial

The interrogation under torture, or “quaestio”, was introduced in the early thirteenth century by secular courts as an extreme means to obtain confessions.

In Inquisition trials, torture was introduced by Innocent IV with the bull “Ad extirpanda” on May 15, 1252.

To justify the use of torture, evidence had to be presented, corroborated by the testimony of at least two “irreproachable” individuals (“omni tamen exceptione maiores”). Some social groups (academics, knights, nobles, clergy, etc.), immune to torture under secular law, did not enjoy this privilege in heresy trials.

The use of torture was prohibited in the case of pregnant women or those who had given birth within the last forty days, the elderly, individuals under fourteen years of age, and physically impaired persons (cf. “Directorium Inquisitorum” p.594, “Questionum medico legalium tomi tres,” 1726, p. 488).

There are numerous documented cases in which, after receiving instructions from Rome to proceed with torture, inquisitors themselves were informed of the impossibility of proceeding because, after a thorough examination, the physician judged that the accused was not in a condition to endure it (cf. letter from the Cardinal of Santa Severina to the Inquisitor of Bologna, May 1, 1593, BA, ms.B-1861, f.175; or the sentence against Francesco Vidua of Verona, April 25, 1580, TCD, ms. 1225, f.184; or the letter from the Roman Congregation to the Inquisitor of Modena, January 24, 1626).

After Nicolas Eymeric (Spanish theologian and inquisitor) wrote the Directorium Inquisitorum (completed in 1376), some steps were taken back from this practice:

The torture is a fragile and risky instrument, often incapable of leading to the truth. Indeed, many, thanks to their mental and physical strength, manage to endure torments, making it impossible to extract the truth from them; others fear suffering to such an extent that they are willing to lie to avoid it.

(cf. “Directorium Inquisitorum,” p. 483)

6 • Abuses

What has been reported so far is the regular conduct of inquisitorial activities.

And you might ask: “What about all the stories I’ve heard of injustices, summary trials, and abuses?”.

The answer is very simple (and I already hinted at it last time): these are abuses (meaning anomalies, malfunctions compared to ordinary behavior).

As evident from numerous correspondences that have come down to us, the risk was (naturally) higher in provincial courts: in these cases, officials were often overloaded with work, poorly trained, and sometimes insufficiently motivated and unsuited to the tasks assigned to them.

With the relevant documents in hand, when the authorities in Rome became aware of such irregularities, they took corrective action to ensure the observance of prescribed procedures and to address cases of judges displaying evident negligence or lack of knowledge.

Conclusions

Based on the limited scope of my research, academic studies portray an Inquisition far more restrained than the one depicted in movies, Instagram memes (and the rhetoric of some anti clerical individuals with a biased viewpoint).

Certainly, no one denies that, even during the historical period of the Inquisition, there were disobedient followers of Jesus.

Just as in 2019, there were disobedient followers of Jesus.

And just as when Jesus preached in Galilee, there were disobedient followers… starting with the “Twelve,” whom He Himself had chosen to “be with Him” (Mark 3:14).

sale

(Winter 2018-2019)